Artist and writer Frédéric Delanglade (1907-1970, FR) started painting in 1928. His first exhibition in 1932 prompted the remark, ‘He paints like he dreams.’ In 1939, Delanglade organised the exhibition Le Rêve dans l’art et la literature (Dream in Art in Literature), which featured drawings by the mentally ill. During the war, he was captured by the Germans. Having escaped from the Nazi camp at Bar-le-Duc, Delanglade fled to Marseille in 1941, where he joined other Surrealist artists hoping to escape Europe and participated in the creation of the Surrealist deck of Tarot cards. In 1942, he was hiding in an asylum in Rodez having Antonin Artaud as an inmate there.

Jeu de Marseille

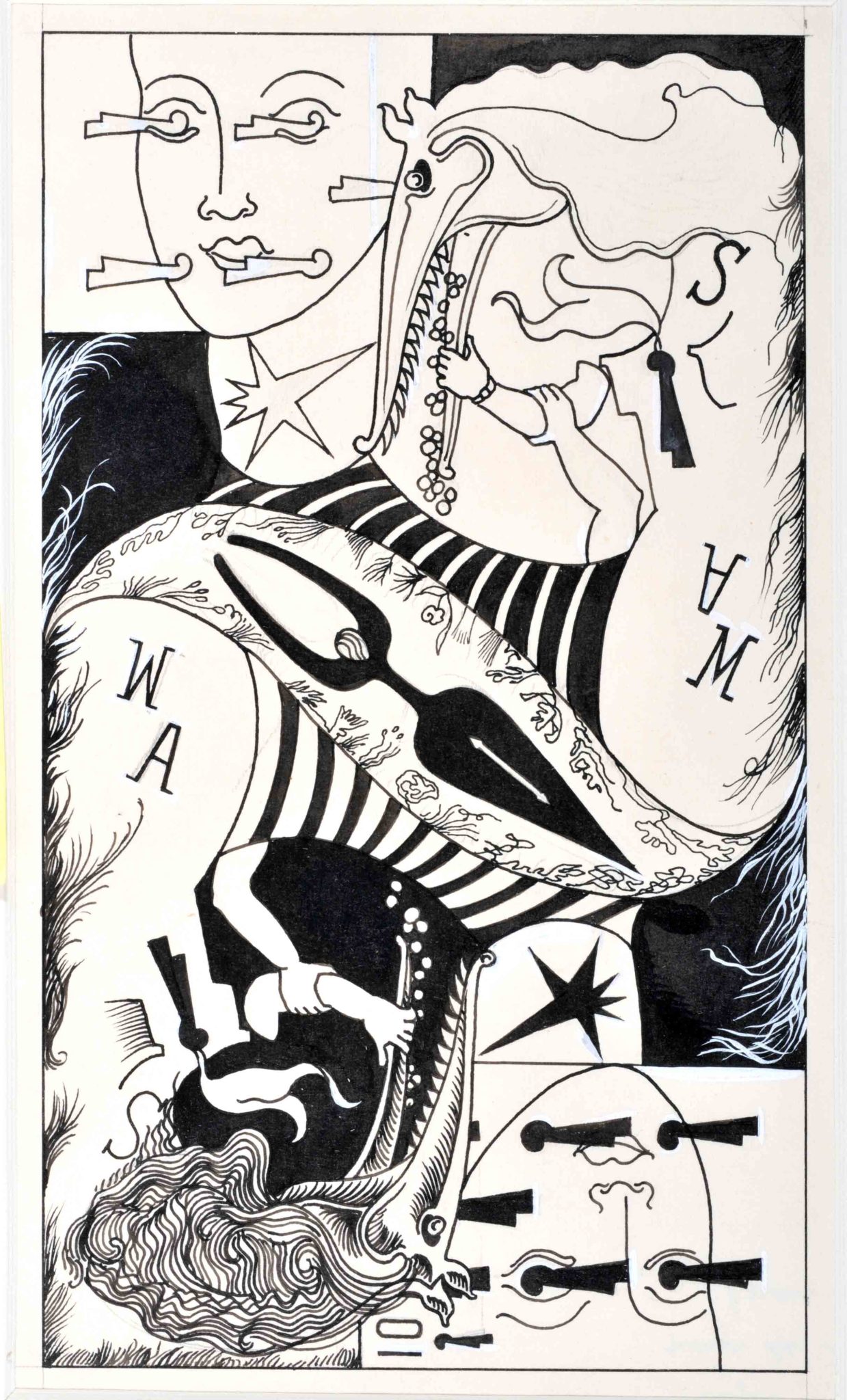

Among the many works by the artists and writers gathered at Villa Air-Bel, the most outstanding is certainly the Jeu de Marseille – a nod to the famous ‘Tarots de Marseille’, which André Breton was studying at the time. The Surrealists reinvented the iconography of a classical deck of cards in terms of the movement’s favourite figures and symbols. The suits became became the flame of Love (represented by Baudelaire, Stendhal’s Portuguese nun, Novalis), the black star of the Dream (Lautréamont, Lewis Carroll’s Alice, Sigmund Freud), the bloody wheel of the Revolution (Marquis de Sade, Lamiel, Pancho Villa) and the lock of Knowledge (Hegel, Hélène Smith, Paracelsus). A random draw determined who would design the different cards: Victor Brauner (Hegel and Hélène Smith), André Breton (Paracelsus and the Ace of Knowledge), Jacques Hérold (Lamiel and Sade), André Masson (La Religieuse portugaise and Novalis), Max Ernst (Pancho Villa and the Ace of Love), Jacqueline Lamba (Ace of Revolution and Baudelaire), Wifredo Lam (Alice and Lautréamont) and Oscar Dominguez (Freud and the Ace of Dream). The joker was based on Alfred Jarry’s drawing of Father Ubu, while Frédéric Delanglade designed the backs of the cards. Frédéric Delanglade was then tasked with standardising the sketches by redrawing them in a continuous line. In 1943, they were published for the first time in New York in the third issue of Revue WW and then edited in 1983 by André Dimanche.