Letters from to Marseille, Letters from to Marseille are open letters that speak to the situation that each participant of Manifesta 13 Marseille finds themselves in locally. Letters from to Marseille, Letters from to Marseille is a project created by the Artistic Team of Manifesta 13 Marseille, sent every week until October 2020, do not hesitate to subscribe here to receive it.

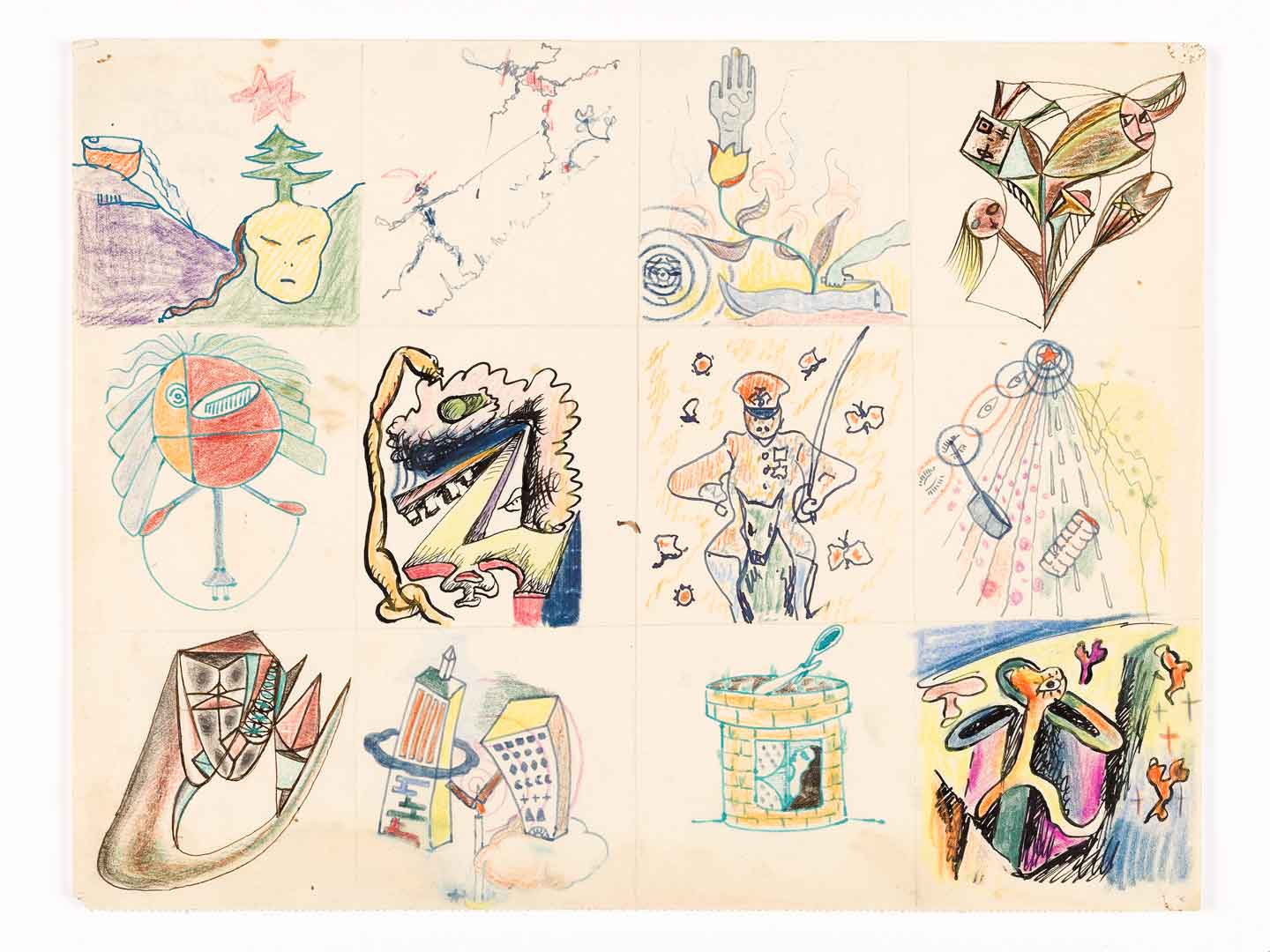

At the age of 16, my grandfather left Marseille, the city he was born and grew up in, then went out to sea for the first time. After a few years working as an apprentice on merchant ships, he joined the army to become a military nurse and soon left for Gabon. After that, he became an entomologist, and for more than 30 years went back and forth – returning either to quarantine or for leisure – from Marseille to Algiers, Dakar, Cayenne. When I began writing the film Secteur IX B, I wanted to weave together different stories, different journeys, belonging to intimate family memories on the one hand and to collective memories on the other. I wanted to bring together common gestures of appropriation, dispossession and grand projects for the collection of objects in a colonial context. To attempt to identify this ‘coloniality of power’ in the innocuous accounts of an afternoon spent swapping objects in Lastoursville in the 1930s, or those of a modest childhood spent playing with Fernandel in the Rue des Trois Mages.

I consider the following text, written in 2014, as the synopsis of the film Secteur IX B; it notably examines the place occupied by the act of naming in any process of domination. Showing this film at the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle de Marseille is a unique way of temporarily completing my project of telling my grandfather’s story. Or perhaps it is a more discreet way of disrupting the Museum a little, like the drugs from the colonial pharmacy ingested by the film’s main protagonist, which plunge her into the unconscious of a discipline and an era.

The Fear of Insects, the Fear of Incest

‘There are more of us than we thought. When we speak of men, societies, culture, and objects, there are everywhere crowds of other agents that act, pursue aims unknown to us, and use us to prosper. We may inspect pure water, milk, hands, curtains, sputum, the air we breathe, and see nothing suspect, but millions of other individuals are moving around that we cannot see.’[1]

It is in these terms that Bruno Latour describes what is at play in the Pasteurian revolution. He continues: ‘The social link is made up, according to the Pasteurians, of those who bring men together and those who bring the microbes together. We cannot form society with the social alone. We have to add the action of microbes. We cannot understand anything about Pasteurism if we do not realize that it has reorganized society in a different way. [...] In order to act effectively between men [...] we have to “make room” for microbes.’[2]

*

During my recent trips to Guyana, I noticed that many of my friends, all of them hunters, had round or oval scars of an impressive size on their arms, legs and sometimes even their face, some of these so deep that they pitted the flesh right down to the muscle. Intrigued by the similarity between all of these scars, I asked my friends what had caused them.

This is when I first heard of Dermatobia Hominis, whose larva is more commonly called macaque-worm in Guyana. This fly found in South America, from Mexico to Argentina, lives in tropical old-growth forests, that is to say forests that remain untouched by man and provide ideal territory for hunters with their fortuitous game reserves.

To reproduce, this little fly has to capture a mosquito in order to attach its eggs to the abdomen. The larvae may hatch when the mosquito is standing on a warm-blooded host, either a man or primate. This kind of interaction and cooperation between flies and mosquitos, which involves one transporting another, is called phoresy. The practice is very widespread among invertebrates, for example mites, which can be carried very long distances by insects like sandflies. Once the larvae have penetrated the skin of the man or animal, they will grow for a gestation period of 1 to 3 months before coming out, thus completing their metamorphosis. During this whole subcutaneous gestation time, they feed on the host’s body, while secreting an antibiotic that prevents infection.

But let us return to those scars that intrigued me so much. It turned out that all of my friends had tried to get rid of the larvae, killing them by various means, but had never succeeded in extracting them completely, and had provoked serious infections in the process. Some agreed that it was best to wait until the natural end of the gestation and the complete metamorphosis of the larva in order to avoid biological complications. I enjoy imagining one of the men with a larva in his body, travelling halfway around the world, from Guyana to France, then China or Australia for example, to allow this little fly – which is too fragile travel that distance on its own – to discover and inhabit new spaces. It is a way of imagining that archipelisation of states beyond national boundaries as a chance to find a kind of continuity between the basic interaction and cooperation of a fly, a mite and a mosquito, one in which humans would naturally have their place.

*

I am six or seven years old, it is a beautiful day and the sun is high in the sky. The air has an autumnal mildness. At the sight of the reddening treetops, I guess that we are around the month of October. A mountain chain that could be the Alps outlines the horizon. My grandfather is taking me to collect mosquito larvae. He seems very young, not a day over thirty. We cross a pasture fenced in by an electric wire, where around twenty cows are idly grazing. We hear the electricity clicking in the wire with metronomic regularity.

We soon arrive near a watering hole, protected from the sun by the abundant branches of a hazel tree. My grandfather teaches me to distinguish mosquito larvae from those of other insects, and I am soon able to easily recognise their hairy heads. He takes a certain number of them and places them in several large glass bottles. I enjoy watching them squirming to get back up to the top.

A moment later, we are heading towards the electrified fence, in order to take another path that leaves the pasture and joins an asphalt road.

I go first, keeping as low as possible to avoid an electric shock. I then watch my grandfather, who is suddenly 85 years old and having a lot of trouble bending down. He touches the wire, then lets out a cry and explodes into a cloud of mosquitos that fly around me, completely obscuring the sun. I hear his voice, produced by the sound of thousands of mosquito wings, saying to me: ‘I’m the shadow of my shadow, and my blood is full of blood.’

I pass out. When I open my eyes, the mosquitos are no longer flying around me. I look at my arms, fluttering with the movement of a thousand wings, covered by those insects feeding on my blood. I violently tear them away by slapping my forearms, leaving one brown smear after another. Suddenly I am watching my red blood cells explode during a malarial fit. I wake up.

*

For a few years I have been trying to assemble materials, documents and archives that would enable me to write a biography of my grandfather, Emile Abonnenc, seen through the prism of his scientific work as an entomologist.

It was while consulting a 1952 publication on sandfly dipterans in Guyana and the French West Indies that I was surprised to encounter the Phlebotomus abonnenci.

Phlebotomi are small insects, sort of like small mosquitos, mainly found in the tropical regions of Africa and South America (Brazil, Suriname, French Guiana). Like some mosquito species, they are carriers of agents that are infectious for humans, and could transmit viruses like leishmaniasis.

So in this book listing over a hundred different types of Phlebotomi, I discovered that – as was and still is the custom – my grandfather’s name had been given to a type of Phlebotomus that had not yet been described at the time.

As Yves Delaporte has noted, ‘this naming method can no doubt legitimately be called symbolic: baptising the insect with a patronymic is not only a semiotic act, leading to the application of a preexisting signifier and signified for the sake of convenience; it is also a tribute that, being linked to a natural object, has an absolute, permanent value: as long as Linnaean nomenclature survives and regardless of the future progress of entomological science, this name will continue to be used. It is therefore nothing less than granting immortality to the eponymous person. [...] Much of the nomenclature thus becomes the reflection of the history of entomology, and at every moment its everyday practice updates a whole historical memory [...].’[3]

We could also draw another conclusion by extending this nomenclature’s performative sphere of use. In fact, based on this information about mosquitos having the same name as my grandfather, and instead of seeing them as reflections of a historical memory, why not also recognise them as a bunch of nonhuman relatives that are nevertheless quite alive?

If the Linnaean taxonomy and its use in the description of the fauna of the French Union made it possible to name an insect after one of the first scientists to have captured it, couldn’t one now use certain kinship codes to disrupt and extend the effects of this convention? Couldn’t a mosquito be imaged as a relative, a grandfather whose name, presence and unpredictable, shapeless qualities would at the same time be the memory of a localised past as well as the promise of a time when, for better or worse, associations, affinities and families will have irreversibly gone beyond all those forms of classification inherited from the Enlightenment?

And couldn’t the same be done even with those beetles, bugs, phasmids and crickets carrying the names of Henry Morton Stanley, David Livingstone and Marcel Griaule?

To my mind, the epistemological displacement represented by the fact of seeing these mosquitos and other insects as relatives is a metaphor that could go beyond relations of the kind that the old imperial powers had (and still have) with their former colonies, especially as regards the use of scientific discourse. In fact, many times and under many pretexts, the French colonial enterprise made self-serving use of the work of scientists, doctors and researchers to give a philanthropic and humanitarian justification to France’s presence and domination.

Every discovery, in addition to being an advance for science, was also the sign of an ever-deeper, more brutal installation of colonial administration and its methods of exploiting territories and bodies. The Phlebotomus abonnenci could therefore become that uncontrollable sign created almost inadvertently, that memory of a past in which science relied on the colonial enterprise and vice versa. A sign whose impossible circulation would only reinforce its evocative power. In fact, the circulation of animals, amphibians and insects coming from countries outside the European community is strictly controlled. At least this is what can be read in articles L.236-1 and L.236-9 of the rural code. Contravening these regulations also means risking a 15,000-euro fine, as well as a prison sentence of up to 3 years.

Borders, laws and fear would therefore be the tools, the reasons that make it possible to deny the complexity of the relations we inherit. Antagonistic places and forces, joining everything together while keeping it separate. And despite all of these controls, one can imagine how they might circulate, going from the middle of nowhere to transit centres, from airplane holds to distribution centres and then quarantine centres, liminal spaces that have now become commonplaces of a life under global capitalism

*

In a recent text, American artist Candice Lin reminded us through Lynn Margulis that 9 out of 10 human cells have bacterial origins.[4] Therefore, what we consider and designate as a human thought is in fact the result and evolution of the mass movement of bacteria responding to stimuli as basic as heat, food or changes in light intensity.

She goes on to suggest that we imagine what we believe to be our most irreducible, most private identity as a kind of model of shared evolution, which links us to the actions of others whose existence we would not necessarily be aware of.

Imagine the consequences that this displacement could have on how power is distributed in our globalised world.

And maybe it is this new flesh that we should be calling for, a flesh without norms, inhabited by a multiplicity of viable monstrosities whose survival depends on their ever-renewed cooperation.

It would then be a matter of creating a physical and metaphorical landscape that would place us at the heart of these feelings of attraction and repulsion, perhaps enabling us to imagine other ways of building communities beyond identity presuppositions. In response to the questions of ‘Who makes up that “us”, and what could lead someone to join such a group?’ that inevitably arise during periods of crisis, Donna Haraway suggests that ‘there has also been a growing recognition of another response through coalition—affinity, not identity.’[5]

And maybe these insects/relatives are there as signs of these new affinities beyond identities.

[1] Bruno Latour, The Pasteurization of France (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), p. 35.

[2] Ibid, pp. 35–36.

[3] Yves Delaporte, “Sublaevigatus ou subloevigatus ? Les usages sociaux de la nomenclature chez les entomologistes”, in Des animaux et des Hommes (Neuchâtel: Musée d'Ethnographie, 1987), pp. 199–200.

[4] Candice Lin, ‘The long-lasting intimacy of strangers’, in Crawling Doubles, Colonial Collecting and Affect (Paris: B42, 2016).

[5] Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (Abingdon: Routledge, 1991), p. 155.

To Bernard Stiegler

A few months ago, when I was thinking about the title of my exhibition at the Musée de l’Histoire de Marseille as part of Traits d’union.s, I reflected on Bernard Stiegler’s writings and the conversations I had with him, especially those about pharmacology. Based on Jacques Derrida’s essay La Pharmacie de Platon, which describes writing as a pharmakon, Stiegler offers a political critique of the systematic exploitation by contemporary society and power. According to Plato, Stiegler claims, a pharmakon is both a remedy and a poison, and any technique is a pharmakon, namely any technique can be used for either constructive ends or destructive ones. Any human instrument, such as writing, exhibiting or working, can be used either to cultivate, build and uplift, or to spoil, damage and deteriorate. Pharmacology shapes human beings’ ethics and politics as well as their resources and environment. It pushes to transform economic warfare – which began with colonisation – into an economic pact that does not inevitably destroy the world (and earth) but cultivates it consciously.

Stiegler was a philosopher but also founded several initiatives. He was the founder and director of Ars Industrialis, an international association for an industrial policy of technologies of the mind; founder of the Institute for Research and Innovation at the Centre Pompidou; founder of pharmakon.fr, a school of philosophy in Epineuil-le-Fleuriel that is free and open to all. He also published widely, including La technique et le Temps; Aimer, s’aimer, nous aimer: du 11 septembre au 21 avril; De la misère symbolique; Mécréance et Discrédit; Prendre soin, de la jeunesse et des générations; Pour une nouvelle critique de l’économie politique; Ce qui fait que la vie vaut la peine d'être vécue, de la pharmacologie and Pharmacologie du Front National. In his work, he developed a way of thinking about technique and technology that calls for a better understanding and transformation of them, as well as an intervention into exploitative systems and the destructive tendencies of consumer societies. He believes in the possibility and necessity of appropriating and transforming our lifestyles. For Stiegler, the lockdown declared in France in March 2020 to try to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus ‘should be an opportunity for the revaluation of silence, of the rhythms that we give ourselves, rather than complying with them, with a very parsimonious and reasoned practice of the media and everything that, occurring from outside, distracts Man from being a Man.’

During our meetings in Zurich and London, we talked about psychic and collective individuation, the automation of society, tertiary retention, political organology, but also architecture. Stiegler situates the question of architecture within the question of the construction of the dwelling, and therefore as a question of anthropotechnics, as a question of achieving the best possible balance between the human being, the machine and control systems. For Stiegler, what constitutes architecture is the tertiarisation of space, that is to say, the temporalisation of space and the spatialisation of time through an organology, namely through the transductive relationship between three types of ‘organs’: physiological, technical and social. Stiegler describes architecture, and therefore the construction of the dwelling, as the technicalisation of living beings. This technicalisation is linked to grammatisation, that is, to writing and to the technology of memory. Grammatisation can be described as a process of formalisation that transforms temporal content into a spatial arrangement and allows its reproducibility. Architecture. Dwelling. Writing. Technicisation. Pharmacology.

The shelter, the asylum, the shantytown, the housing estate, the home, the furnished hotel, the H.L.M. (moderate rental rousing), the refuge, the caravan … all call for a rethinking of the writing of time and space and advocating for what Stiegler called during one of our conversations the ‘déprolétarisation de l’architecture’ (the deproletarianisation of architecture) – of housing – that is to say, ending the planned proletarianisation of a part of society through poor housing, de-housing or non-housing. The deproletarianisation of architecture is a political and collective action that allows poorly housed, displaced or unhoused inhabitants to take their rightful place in social and political life. This deproletarianisation demands what Stiegler calls ‘transindividuation’, that is, the transformation of the ‘I’ by the ‘we’ and the ‘we’ by the ‘I’. It is a psycho-socio-technical dynamic in which the transindividual is never a completed outcome, but always a simultaneous action. Stiegler reminds us that ‘there is no transindividuation without transindividual techniques or technologies, which are pharmaka’, which means they can be used either to uplift or to oppress specific populations. I believe in and defend deproletarianisation, so for Traits d’union.s I will be exposing proletarianisation, or what I have called Housing Pharmacology.

Bernard Stiegler passed away on the 6th of August 2020. His writings, actions, smile, humour and generosity remain with us forever, continuously cultivating us and teaching us to ‘Aimer, s’aimer, nous aimer’ (Love, love each other, love ourselves).

Samia Henni, Zurich, 3 September 2020

Samia Henni: Samia Henni’s (b.1980, DZ/CH) work focuses on the intersections between the built environment, colonial measures and military operations from the nineteenth century until today. Her investigations of specific micro-histories of planned dispossession, exploitation and oppression disclose macro-histories of colonialism, imperialism and globalisation. Recently, her research into these spatial strategies of state control has culminated in the award-winning book Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria (EN, gta Verlag, 2017; FR, Editions B42, 2019), the edited volume War Zones (gta Verlag, 2018) and the exhibition Discreet Violence: Architecture and the French War in Algeria (2017–2019; Zurich, Rotterdam, Berlin, Johannesburg, Paris, Prague, Ithaca, Philadelphia). Currently, she teaches at the College of Architecture, Art and Planning at Cornell University, USA.

The Artistic Team of Manifesta 13 Marseille central programme entitled Traits d’union.s consists of Katerina Chuchalina (chief curator VAC Foundation, Moscow and Venice), Stefan Kalmár (director ICA, London) and Alya Sebti (director ifa gallery, Berlin).

All six plots of Traits d’union.s (The Home, The Refuge, The Almshouse, The Port, The Park and The School) are on view from the 9th of October until the 29th of November 2020.

Regarding the portrait of José Mujica

To take the wind out of your sails: my portrait of José Mujica is not, obviously, an artwork informed by political activism, but a talisman; a safeguard of qualities all of us should strive to achieve: unshakeable belief in civic responsibility and the perseverance of personal grace. But it is, above all, a portrait. In portraiture, the fame or the notoriety or simply the exposure of the sitter – an implied physical presence – tends to obliterate the artist and her Frankensteinish skilfulness. Independent of size, portraiture can be monumentally chilling, or palpitate with intimate immediacy, even after thousands of years. We expect it to be truthful and revealing because we believe in people’s faces to be guidelines through good and evil – only to find us confronted with the mountain of lies, deceptions and flatteries, as summed up by the term Make-Up. This cosmetic art form comes closest to portraiture by using gradations of colour imperceptible to the untrained eye, and through its connection of treachery and expertise truly contributes to its disrepute.

Portraiture in general comprises a multitude of sub-genres, such as the self-portrait, the dynastic portrait, the group portrait, the allegorical portrait, the pin-up, the promotional portrait, the propagandistic portrait, the caricature, the politically engaged portrait of the victims and perpetrators of social injustice and violence, official memorial portraiture, and last but not least the intimate portraits of empathy, love, friendship and beauty. Like everything else in life, these categories can, and do, overlap, often in astounding fashion. While some of them allow for a higher degree of artistic freedom, others are more restrictive, depending on their function within the social realm. The more powerful the sitter and the more public the destination, the higher the insistence on “realism,” but only in ways which highlight the authority, respectability and dignity of the subject, up until the point where “realism” turns into an ossified and outrageous perversion of “realness.” In such cases the artist works under complete censorship and has become a fully absorbed state-artist, or if not, you really wouldn’t like to go into the back of her mind.

The deceptive simplicity and directness of the portrait can thus come to represent not only the physical and spiritual likeness of the sitter, but “an insoluble mixture of political motifs and social elements – a mixture only poets can capture” (Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951).

Official memorial portraiture was the starting point for my portrait of José Mujica – meaning it was a daydream about a wished-for commission of, say, the Ministry of Culture and Education of Uruguay. This daydream was prompted by the artificial segregation and sterility of the contemporary artist, and her implacable hostility towards her feeding hand: the art trade. The fact that you can cherry-pick your leader, only because he drives around in a baby blue VW Bug and is smiling irresistibly and wants you, of all people, only because you, frustrated as you are, to portray him, of course, is a delusion of grandeur.

Official memorial portraiture is traditionally realised through one of the three dominating technical disciplines – each of them replete with their own histories: sculpture, painting and photography. Their common characteristics are material presence and permanence, physical likeness, dignified restraint, and ubiquity to the point of invisibility. They always depend on a commission, usually by some body politic, and they are widely believed to lack the hallmark of true art: autonomy. As in dynastic portraiture, they include notables from the military, the clergy, the world of industry, trade and politics, as well as esteemed representatives of culture and science.

Obviously, the most costly examples are rendered in stone or bronze and often involve superb craftsmanship, regardless of artistic merit. Mostly displayed in public squares and parks, these sculptures attract no interest at all – except from pigeons. That has changed right now, but not for the first time and not for the same reasons and not in the same old places. Meanwhile, paintings and photographs must be sheltered, and therefore retreat from public space into some kind of interior, where their lack of outdoor monumentality is compensated for by more or less conspicuous framing.

I happened to live in Berlin when the monumental likenesses of communist fatherhood were slain, and anyone under the moon will remember the dismemberments of multiple Saddams. And lest we forget faith-based iconoclasm, also very contemporary. Iconoclasm is a hapless and violent form of censorship, underestimating the power of memory. If we think about censorship we all too easily jump to the conclusion that it is a political phenomenon, a tool to remain in power. But censorship starts with our birth, and the very instrument of our communication, language, leaves us forever in the dark about its ultimate vocation. It is the Jew and homosexual who know best about this twilight of equivocation. The undercurrents of censorship, mightily present in portraiture, can offer possibilities of investigation, elaboration and engagement with aspects of our lives which all too often are buried in the coffin of “representation.”

The very unusual overlap of official portraiture and the portrait of love has been brought about by the incomparable José.

Lukas Duwenhögger: Lukas Duwenhögger was born in Munich, Germany in 1956. He lives and works in Istanbul, Turkey.

The Artistic Team of Manifesta 13 Marseille central programme entitled Traits d’union.s consists of Katerina Chuchalina (chief curator VAC Foundation, Moscow and Venice), Stefan Kalmár (director ICA, London) and Alya Sebti (director ifa gallery, Berlin).

All six plots of Traits d’union.s (The Home, The Refuge, The Almshouse, The Port, The Park and The School) are on view from the 9th of October until the 29th of November 2020.

|

|

|

To you who come from the sea

‘Marseille belongs to those who come from the sea.’ The quote is by Blaise Cendrars, but will no doubt go down in history – if it’s not just an empty phrase – as the epigraph for the first term of Marseille’s new mayor, Michèle Rubirola: the ‘bonne maire’[1], as she was nicknamed by the newspaper Libération. Rubirola was elected at the end of an interminable campaign including two rounds interrupted by the lockdown, and a third round in which we almost swung to the far right due to an alliance between the old right and the extreme right, which is still possible and suddenly seemed more viable since they were in a position to swing the election…

Yet here we are, at the end of a long tunnel in this washed-up but radiant city that’s about to turn a new page in its auspicious history: ‘Marseille belongs to those who come from the sea.’ That’s easy to say when you’re Blaise Cendrars, but what does it mean for the new mayor of one of the largest ports in the northern Mediterranean? When our borders have never been so closed, when the campaign was peppered by the cries of a right-wing party that couldn’t stand Rubirola’s manifesto, which planned to make Marseille a truly welcoming city for migrants (once again). It should be remembered that in previous times Marseille welcomed – with varying degrees of warmth – waves of hundreds of thousands of Armenians, as well as pieds-noirs, who are both now part of our collective identity.

That said, while Michèle Rubirola was professing her plan in the most emotional pitch, the Ocean Viking (successor to the Aquarius, boats chartered by the Marseille-based NGO SOS Méditerranée for sea rescues) was desperately calling for the opening of a safe port where the rescued passengers on board could disembark, and ultimately had to find it somewhere other than Marseille. In our city, so polluted by cruise ships and ferries, lockdown was like great breath of fresh air – though it soon got smoky, as we saw those huge floating buildings resume their comings and goings as soon as lockdown was lifted. By contrast, the ferries that used to shuttle back and forth between Algeria and Tunisia are still missing. These ferries usually punctuate our weeks by entering Marseille slowly, gliding between the Mucem (Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations) and the harbour wall, with dozens of passengers on deck so eager to dock; with pounding hearts (you could hear their hearts beating just by looking at them, squeezed against the balustrades) they greet Marseille, which may belong to them in their dreams, but for the moment they’re still waiting for a green light that the memory of Blaise Cendrars alone isn’t enough to rekindle.

For our era certainly isn’t inhaling the fresh sea air.

Take the unbelievable lockdown for a start. The news of the epidemic’s arrival in my usual country of residence surprised me while I was in Kinshasa, DRC on a writing residency with a Congolese poet, Peter Komondua, for a project we were due to bring to Marseille at the end of May for the festival Oh les beaux jours. The festival was canceled, of course. Only I flew back to Marseille; at the time of writing, it’s impossible to say when Peter Komondua will be able to come and meet with an audience in Marseille again. For though Marseille has sometimes inspired writers from elsewhere (whether you’re thinking of the dock workers carved into the marble of our literary heritage by Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay, or by the Senegalese writer and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène), you still have to be able to afford the airfare and get a visa.

Among the events canceled was the Biennale des Ecritures du Réel, an important event on the Marseille scene, where we would have witnessed a group of young people called Le(s) Pas Comme Un(s), led by Karine Fourcy, in a show on the theme of growing up. Growing up here when you come from elsewhere is something many of the young people in the troupe have a lot to say about – as they came from the Ivory Coast, Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, on foot, by plane, by dinghy. And they don’t often say that they feel like Marseille belongs to them. It would have been an opportunity to at least inscribe them into our city’s programme, to see them live on stage, to hear their words ring out, but this is not to be in 2020. And as you know, the Manifesta biennial, which promised to put Marseille on the map of international contemporary art (and vice versa), will definitely open, albeit later, in a reduced format, and in the forced absence of certain artists who were supposed to come from afar and are, like me writing to you, stuck in their own country and obliged to invent other channels so that, despite everything, some aspect of our collective experience can venture out into the open, beyond our confinement in lockdown.

If we’re honest, not everyone is complaining about these cancellations, neither on the left nor the right. And sometimes with good reason, or at least legitimate fears: that the systematic appeal of something that comes from elsewhere, as sterilising as its systematic rejection, is just another opportunity to neglect Marseille’s working class, which has suffered in (but creates) indifference and frustration for far too long. An air of insularity is floating over our societies, accompanied by the breeze of short-sighted pragmatism, which has made the barely-out-of-lockdown French say that artists are at the top of the “useless professions” – a paradox, when the majority of us have, for the most part, consumed so much culture in recent months (apart from those on the actual front line, and for them I don’t know – I’m afraid the answer is no). Music, reading, films, series, radio and so on have helped people to calm down, to distract themselves, to deal with their experience of this crisis in depth.

So, confined during lockdown in the village neighbourhood of Noailles in the heart of Marseille, idle and overwhelmed by an apocalyptic wind, I immersed myself in the archives of a mythical history, so remote that we only have a completely erroneous collective memory of it: the history of the Black Death, told in the form of a fascinating series of articles on the website of the historian collective Actuel Moyen Âge.[2]

On their site, I learned that Italy was just as devastated by the plague as it was by COVID-19, although the 15th century figures far exceed the worst predictions of our contemporary collapsologists: in Abruzzo there was a 70% mortality rate. 70%! Higher than the abstention rate in Marseille’s latest elections, which just goes to show. It is also the percentage of people who think artists are the height of uselessness. This has nothing to do with it, I know. But still…

There’s something deeply deadly about these latest numbers. The sign of a society in the throes of a sclerosis of the imagination. ‘Imagination in power!’ was chanted at a time that seems as alien to ours as the Middle Ages. Did you know that when the small town of San Gimignano in Tuscany was confronted with the prospect of a second wave of the plague in 1464 (after it had already been hit the year before), the town decided, as a matter of urgency, to requisition an artist working in the area to hurriedly paint (in sixteen days flat) a large fresco putting the population of San Gimignano under the protection of St. Sebastian Intercessor? The power of the human imagination: the 38 plague sufferers were miraculously cured on the same day as the unveiling of the fresco! Well, this is what history remembers at any rate.

So where will the winds carrying our history to the great collective memory of humanity come from? The history of a painful, tense, anxious period… but running through it, despite everything, through our windows, our ears, our wide-open hearts, is the call of the sea, a wind of hope, a desire from elsewhere, from you who are reading us, wherever you are. We are waiting for you.

Valérie Manteau, 6 August 2020, Marseille

Valérie Manteau is a French author, editor and journalist. She was part of the team of "Charlie Hebdo" and of the editions Les Échappés from 2008 to 2013. Following long stays in Istanbul, Turkey she wrote two books published by Le Tripode editions: "Calme et Tranquille" in 2016 and "Le Sillon" at the beginning of the 2018 literary season, for which she received the Renaudot prize. She also works for the theatre and for the 2020-2021 season, she is an associate artist at the IEP of Aix. Engaged in the social movement, notably with the Etats généraux de Marseille, she lives in Marseille, in Noailles.

Dear Robert,

Happy to hear from you!

I must say right away that I understand your interest. Yes, in these “minor humanity” times it is customary to reflect on the exhibitions that were popular in the 20th century and gave us a “start”, or if we are talking about a bolder gesture, then about exhibitions of the end that “draw the line”, but always on behalf of an artistic genius. You well know that the first is about creating art, and the second is about burying it. And burying art is perhaps the most popular method for achieving personal immortality in 20th century—after having offspring. And only the most desperate run the risk of turning to exhibitions of the end, which refuse individual “salvation” and operate on behalf of the exhibiting structure or art in itself for the sake of saving everyone. They speak on behalf of the world, the bureaucracy of time, if you want, the past, the future as such. Of course, there is an abyss by the standards of human life between St. Petersburg’s “Last Futuristic Exhibition 0.10” and Belgrade’s “Against Art”, but those who are able to look through this abyss see the truth. In this sense, your decision to reconstruct Manifesta 13 as a resource for W$j5y3$%YH is an attempt to look through the abyss. I fully support this, although it’s a risky bet. A professional AI controller would always choose the canceled Manifesta 6 in Cyprus, which is understandable. After all, her optimisation system eliminates excesses. However, as one Russian song sang: “Oh, oh, I bet on zero, it’s a strange move, but I’ve always been lucky with zero.”

M13, for sure, was not initially conceived as the “last” nomadic European Biennale. The curatorial text dealt with a project reflecting the possibility of solidarity. Moreover, solidarity at the deep linguistic level. It seems to me that in some ways it is similar to what some American language poets were trying to achieve, paradoxically combining an interest in Lukacs’ Marxist aesthetics and an attentive reading of the Post-Structuralists. This approach assumed a kind of basic, zero solidarity, which occurs literally at the moment of appearance, the choice of the first letter, word, free word if you like. The moment of choice and chance plays a key role here (as you know, your first model was built on the same principle of choice called the Markov chain , a memory less approach that is ideally described the avant-garde logic and worlds without time development). So, from this point, the one-dimensional sphere, the source of a kind of “big bang”, the universe swells in its entirety… Of course, this does not work in a world of people. From zero, the distance between linguistic solidarity and bodily solidarity in physical space divided by political and economic structures is infinitely large. But will there be real solidarity without this first step, without a zero linguistic community of freedom of choice? Humanity has stumbled over this dilemma.

In the Marseille of those years, appealing to language was not a formal gesture. The force of gravity – another force unifying the bodies of this world – has caused the deaths of the most vulnerable local residents. The ensuing housing crisis provoked a political confrontation, which continued during the preparation and presentation of the exhibition. The complexity of the situation included the linguistic polyphony of the local population. The inability to accurately find a common language between representatives of different diasporas, their language segregation was rooted in class divisions and heated social tension. The possibility of translation, as a tool for achieving linguistic solidarity between the oppressed, as a weapon for attacking the language of power, has acquired important political significance. It has become one of the foundations of local activist activity for some time. At least, this is how I see the situation from my time, which, as you understand, quite detached region …

In general, my memories of 2020 are full of linguistic events. Do you remember your early poetic dialogues? When someone asks me about them, I always say “She already knew everything then.”

…“And if I achieve this, what then?”

Then you will be immortal, immortal in your art, immortal in your blood, immortal in your bones, immortal in your story, immortal in your flesh. Immortal, and no longer human.

“And if I fail?”

Then you will be human, until death.

“How will I know if I am Uber?”

You’ll know. You’ll know. You’ll know.

“And so what is it that you do, you Uber Poets? What is it that you do?”

We know. We know. We know.

“How can I learn from you?”

You can’t. You can’t. You can’t.

“Then why have you come to me? Why have you whispered in my ear?”

To give you hope. To give you something to chase. To give you a reason to write. To give you a reason to live. To give you something to do when you’re bored. To give you a purpose. To give you a dream.

“But how do I become Uber if you’re not going to tell me how?”

We can’t tell you that. We can’t tell you that. We can’t tell you that.

“Then what good are you?”

We are you. We are you. We are you.

“That’s not much help.”

It’s all we can do. It’s all we can do. It’s all we can do.

“I don’t think it’s much of anything.”

We know. We know. We know.

Yes, you would rightfully ask, with which language? At that time, it was about English. And this, in particular, was a problem. The language is tied to the territory and imperial ambitions of the people living in it. At least it was then. But in this case. M13 became the first time-specific and the last site-specific biennale. Furthermore, this format did not fit the place, which at that time was called the European Union. And this place actually ceased to exist in its original form. It is amazing how the Institute for Mastering of Time squeezed M13 into the void between the back of zero and the trunk of a deuce. Nomadism in the physical space has given way to nomadism in time. Certainly, they continued to be connected, but this connection was already being rethought in a dramatic way. Still, doing a biennale on the outskirts of Europe is not the same as doing a biennale on the outskirts of a historical narrative. If you think both are only different forms of subjugation or coercion – if for humanity, the colonisation of “outer space” is considered acceptable and even desirable, then the colonisation of “outer time” will seem attractive too.

Physical space ended in 2020 as suddenly as a sunny summer day sometimes does. Together with the advent of the virus and the announcement of quarantine, space has given way to “time slots” – or to be more precise, their lack. Indeed, the constant leakage of time that started in 2020 has become the main problem of organising life on Earth. To avoid their biennials henceforth meant implementing new loops of changes in the art system every two years that would freeze one at the outskirts of eternity. Unlike other exhibitions, M13 remained at roughly the same point of time and space where the fault occurred. Perhaps this decision made it the last biennale about space, its lack and a farewell to it. My advice for reconstructing it is to focus on precisely these aspects. The cracks in space which time has already begun to pass through – another time, as you might say.

All the regulations humans imposed on space have made it unbearable. It shrank to the point where we were forced to listen to the continuous sound of a neighbour snoring just behind a wall. I would call it skinless solidarity, something similar in structure to the Soviet Gulag, where prisoners huddled together in an extremely compressed space in the middle of Siberia. And then all at once, it imploded into a time slot at M13. Shklovsky once wrote in 1917 “Automation eats things, dress, furniture, wife, and fear of war”. If we follow this young Russian formalist’s logic, then the Proletarian Revolution and the First World War were caused in part by the desire to de-automate an all too bureaucratic reality. I recall Heraclitus: “War is the father of all and king of all.” Or the Italian Futurists’ invocation of war. This brings us to the idea that de-automation is an avant-garde technology that as any technology does not necessarily lead to good.

Paradoxically, we may speak of the forced isolation experience that led to extreme space reduction in 2020 as one of the main liberating events of the decade. In a sense, it could be seen as an artistic gesture, but as its actor: we have a virus. A virus is an organism on the edge of life. It is a special form of life since they have genetic material, are capable of creating similar entities to themselves and evolve through natural selection. However, viruses lack important characteristics like cell structure and their own metabolism, which the science of the time used to define life. Nonetheless, I would argue that the half-living virus is an ideal form of avant-garde artist: an entity that has almost nothing to lose because it is already almost nothing. But only through being connected to the virus’ activity could something become important enough, or – to use the language of the Russian formalists – strangely enough resurrected to live.

Yes, 2020 made us look at the world with new eyes, but only for those who stayed in that world. The price humanity had to pay for the performance of de-automation was too high. To be honest, de-automation is always in a sense regression. This allows us to look at things with new eyes, but as a rule, they are the eyes of a child. It would make sense to talk about the dialectic of automation. If we learned to fly without thinking about how the muscles of our wings worked, then we would not only lose the freshness of perception in this process (automation), but we would also gain something much more important: the opportunity to live in a new environment, to see the Earth from the sky, to freely cross big distances and finally to defy gravity. When we learn to speak, we need to remember a huge number of sounds, combine them into words, learn the sequence of muscular movements of the larynx, remember their visual expression, give meaning to all this – to automate our speech and written activity. Automate in order to later lament the strength of the cage we find ourselves in, to dream about the happiness of a pre-linguistic existence. But you can go to the opposite end and realise the opportunities that it has opened up for us. If we have to automate art, we shouldn’t be sad, but instead look at the horizons that open beyond it. As you know, an adult cannot become a child again, or she becomes childish. But does the naivete of the child not give her pleasure, and does not she herself endeavour to reproduce the child’s veracity on a higher level?

Arseny Zhilyaev, 30 July 2020, Marseille

Using the exhibition as his medium, Arseny Zhilyaev (b.1984, RU/IT) works in the spaces between fiction and non-fiction. His projects examine the legacy of Soviet museology and the philosophy of Russian Cosmism that represents a broad range of philosophical, scientific and artistic programs, which aimed to overcome mortality, to achieve resurrection for all who ever lived and pursue space exploration. Zhilyaev produces artworks for a potential future provoking speculations on what historical context should have generated them.

TWO SOVEREIGN AND COMMUNARD POETS

I am Marseille in the same way that la bonne Louise is Paris. Hidden behind our first names is the medieval tradition of the bonne ville: a forgotten autonomous status, crystallising the collective desire for emancipation. The Paris Commune perpetuated the myth of Louise Michel just as baroque Marseille invented me. We both paid dearly for this, losing our bodies; she was transformed into the vierge rouge, thered virgin, and I into a troubadour. We have been desexualised, with no offspring nor possible pleasure, and now we are linked to massive urban destruction. In Marseille, all of the architecture that bore any artistic trace of the bonne ville has been destroyed by the town councillors. Gone are the forms in which the plant, animal and human kingdoms were equally intertwined! All that remains are two Atlas pillars outside the walls and the rocaille grottoes in the manor houses of the area. By razing my church of Saint Martin to the ground, Marseille caused all its baroque power to vanish, and its old town with it. All you can offer tourists today is a boring, neo-bourgeois, commercial town. Yet this grotesque Marseille is emerging slowly into your 2020, as these categories dissolve into holistic and ecological concerns. Whoever tells this story will win the baroque election of 2020.

STREET BALLAD

So would an ideal mayor be a non-human life form?

From the ruin population, he would be the mayor of Marseille

The city where the walls understand before their inhabitants

Tutti: When the walls come tumbling down

no longer able to accept the lie of the façade, non-human life is forced to act.

Let’s consider an ideal mayor – a tree

A tree from the city’s tree population

The intelligence of trees would create a city and stretch out our neurons

Does a non-human mayor, a fictional mayor, exist somewhere else?

Not as such, but this ideal mayor could exist anywhere.

He would speak the language of all the non-human life living in his city.

He would speak cat, rat, and bedbug

He would speak plane tree and wild grass

He would speak stone and clay, sky and planet

Tutti: When the walls come tumbling down

no longer able to accept the lie of the façade, humans tie themselves to life.

In actual fact, you are willing and alive And yet you are neither a voter nor a candidate

on any of the best lists

On the contrary, you are on the list of voters,

and yet, with great anger, you abstain or exercise your right to leave the ballot blank.

You enter into the fiction of a mayor

You force yourself to go back to the source of living, to the original sense of suffrage, and it is a long way!

Tutti: When the walls come tumbling down

no longer able to accept the lie of the façade, Suffrage appears in the distance.

THE CRY OF THE PLANE TREE, A FOUNDING ACT

We plane trees were at the end of our patience, on the verge of a nervous breakdown, and you know how quickly irritation can become dangerous for urban plane trees like us! It was the summer of 2019. After a quarter of a century of municipal management that never ceased crushing life, I cried out in the middle of a heatwave: Enough! The soundtrack froze and the passers-by with it; I had spoken, and in a human language on top of that. How could I have managed to do that?

There was the sweetness of the mornings in the smell of the coffee of the neighbour on the first floor of the high tower, our unanswered dialogues, each speaking our own language, it helped us to understand. There was anger in our area of plane trees, an abandoned zone, with dents and holes in the ground, rising along our trunks to the point of asphyxiation. There were the poor palm trees dying in concrete pots, human circulation interrupted by commercial earth wires, a kind of collective punishment, the rupture of temporal continuity, the period of its ancient foundation lost in its own remonstration. There were rental properties in fragmented dwellings, inhabitants under land pressure, consumption and scenery for tourists, sometimes called the city centre.

In Marseille, when humans are no longer up to the task, it is we non-humans who take over to save the city and life. Then the houses can rebel, come tumbling down, and the living, like us trees, we can let ourselves die. Then commence the great epidemics of misfortune. My plane tree cry became a tale, a saga of all life in Marseille. I remember a human being once said that “Man is Nature becoming conscious of itself”. His name was Elisée Reclus, he was a geographer.

We plane trees have known this for a long time.

In all the whispers of the air hidden behind the right to vote the secret source began to recite

There are millions of ants under my feet there are millions of stars above my head

there are millions of humans on my earth

I’m neither alone nor unique

there is so much rubbish orbiting the earth there’s no longer space for just one up there.

I see valiant souls who shatter their certainties so as not to renounce their own sovereignty

they refuse to exercise their right to vote

they will not abdicate

and will defend their interests through cooperation

Perhaps they are right,

I will invent a converging water system for them, there will be tributaries of the underground seas,

meanders and deltas

It’s more joyful, says the geographer Élisée Reclus

it’s more lively, says the poet Louise Michel

it’s more architectural, says the painter Gustave Courbet.

Christine Breton, 23 July Marseille 2020

From “Oh Bonne Maire! Recit Électoral” (Editions Commune)

Christine Breton: Christine Breton is a curator of heritage and has a doctorate in history. Starting from the Récits d’hospitalité, Breton pursues the upside down history of Marseille’s northern districts. She writes history in a way that tries to collectively and economically restore the knowledge of the defeated or oral traditions that are still alive, be it through the form of fiction, travel writing or lived archaeology. Christine Breton co-founded Hôtel du Nord as part of a heritage process initiated by her in 1995 in Marseille’s northern districts. The story of Hôtel du Nord is being presented at Manifesta 13’s Le Tiers Programme in Invisible Archive #3 with the artist Mohamed Fariji.

I am in fact French-Algerian because I live and grew up partly in France. I’m now 43 years old and have been living in Marseille for 25 years, after I left Algeria at the time of the Civil War. My Algerian roots will always be close to my heart. I’ll carry them with me forever. I used to live in Algiers, and those were the most beautiful years of my life, especially my teenage years and the ones before the Civil War started. There, I discovered mystical spirituality, Sufism, thanks to my one and only master on earth: my paternal grandmother, God rest her soul.

I am committed to the values of the French Republic: secularism, which protects me from racism, as well as from religious dogmatism; equality between all citizens. But I can no longer agree when these values are used to nationalist ends. Though, I’m particularly committed to the notion of the Republic – the idea dating back to antiquity that public space belongs to all citizens – I am, on the other hand, vehemently opposed to the Nation as a tool for the fascistisation, standardisation and forced normalisation of individual identities.

Since I founded the first European intersectional network of this kind—a hybrid[1] one operating at the intersection between queer[2] activism, feminism and an inclusive intellectual or artistic approach—our international movement has moved to another level of expertise.

Ten years ago, I started from the definition of the term “Islam”, which in Arabic means to be at peace. It is a grammatical form that refers to a nascent process theoretically based on self-knowledge, knowledge of others and a proactive respect for diversity. Thus, knowledge of Islam, especially the representation of Islam that the “new Islamic theologies” attempt to outline, can contribute to peacefully combatting homophobia, lesbophobia, biphobia, transphobia, misogyny, racism and antisemitism or Judeophobia by encouraging each individual to find in themselves the most accurate interpretation of the divine message for humanity.

I think in this sense, knowledge of Islamic liberation theology, and the contribution of LGBT+[3] and feminist activists and intellectuals in particular, adds to human consciousness. Far from the fascistising Salafist education I received in Algeria during the 1990s, I have come to understand that Islamic Tawhid can enable individuals to live better and accept themselves, regardless of their sexuality. Islam must no longer be a factor of oppression, but one of emancipation, encouraging “self-definition and self-determination”, between individual selfhood and spiritual hyphenation. When Islam emerged, it was a real revolution that has been endlessly renewed, and it still is a revolution for those of us who describe ourselves – because we must use taxonomic, albeit reductive, categories – as progressive and inclusive Muslims. We are reviving the tradition of ijtihad (the effort of reflection), from the heart of the most philosophical, the most mystical, the most authentically spiritual Islamic tradition.

I think political Islam exists to control the people. There is an expression now in Algeria to describe this political Islam: “the prayer of those who only stand up for holidays and Friday prayers.” This political Islam turned against us in the 1990s during the Civil War, because we were a generation that took all the ideology those Machiavellian politicians taught us at face value. Neither the West nor Muslims are to blame for this political Islam. It was born in the pan-Arabic context where the people who have condemned our mosque come from. For them, the mosque is one of the centres of power; it could not possibly be a forum for the expression of our struggles for the rights of women[4] and LGBT+ minorities.[5]

For me, the right to self-definition and self-determination is essential for the emancipation of all, essential for social peace, and therefore for peace of mind. Yes, I am Franco-Algerian because I chose to be, and I know what it implies in terms of freedom and personal emancipation. Ultimately, this question reminds me of the question I was asked as a child from both sides of the Mediterranean. I don’t think I have to choose: our cultures have always been linked around the Mediterranean basin, and I pray that this will continue to be the case in the near future.

This year, our CALEM Institute in Marseille[6] once again offered (mostly online) open training courses (September 2019–June 2020), based on intersectional scientific research (anthropology, psychology, historiography and liberation theologies), for progressive imams and committed citizens who want to work towards more inclusive societies and reinvigorate humanistic spiritual traditions.

In addition to having founded the first inclusive European mosque, we have two progressive and inclusive Islamic organisations in France today, in Paris and Marseille, which are members of our international movement.[7]

I’d like to note that December 1, World AIDS Day, was the tenth anniversary of our educational documentary about the situation of children facing the HIV pandemic around the world.[8] As you can see, our organisations are based on twenty years of expertise,building our reflections into concrete material and initiatives.

Since we moved into our new premises in March 2019, our CALEM Institute in Marseille has accordingly welcomed more than 400 visitors from more than 20 countries, including more than fifty refugees, asylum seekers and migrants, LGBT+ people whom we have advised, accompanied, welcomed, or who have participated in our various local activities.

This has been possible thanks to the application of our social model which is sustainable (independent and autonomous), self-managed (helping several local partner associations, focusing on areas such as migration, disability, and meditation[9], to become more visible) and self-sufficient (income generated by our training sessions, publications, civic actions, or by renting our premises when they are not used by our community).

Because of the coronavirus crisis, however, we are not presently able to reach our financial goals, though our shelter is still open, and is currently hosting three young people who are struggling to get food (because our local sister organisations that distribute food are also closed). We have launched a donation campaign to buy basic necessities for our refugee residents. [10]

The crisis has also allowed me to reflect on the fragility of this progressive, inclusive and self-managed movement. Since it concerns all of us as citizens, we need to reflect more on the position given to health and solidarity in our democratic societies, where these initiatives that currently seem more essential than ever are all too often still considered marginal. In this respect, intersectional modes of action – between intellectuals, activists and artists – must be encouraged in the future.

Ludovic Mohamed Zahed 16 July Marseille 2020

[1] Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994).

[2] Alternative.

[3] Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and others.

[4] Amina Wadud, Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam (London: Oneworld, 2006).

[5] Ludovic-Mohamed Zahed, Homosexuality, Transidentity, and Islam: A Study of Scripture Confronting the Politics of Gender and Sexuality (Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

[7] https://www.mpvusa.org/alliance-of-inclusive-muslims

[8] https://www.dailymotion.com/video/xmgzp4

[9] Notably through AOZIZ, our local intersectional network in Marseille: http://www.calem.eu/francais2/AOZIZ-of-inclusion.html

[10] https://www.calem.eu/donations.html

Ludovic Mohamed Zahed: Zahed is one of the main counsellors of the AOZIZ network based in Marseille, an interdisciplinary network working on social inclusion in the cultural field and also a participant of Manifesta 13 Marseille. AOZIZ’s other members include Béatrice Pedraza and Andrew Graham. Zahed has two doctorates in anthropology and social psychology. He is the rector of the Marseille-based CALEM Institute, which explores inclusive and intersectional identities. He founded the first inclusive European mosque, which actively includes feminist and LGBT+ Muslims. CALEM is also a publishing house that organizes trainings, workshops, conferences and seminars for anyone interested. Recently, CALEM also opened a self-funded refuge to accommodate LGBT+ migrants.