Reena Spaulings first appeared as a fictional character in Bernadette Corporation’s novel of the same name. The artist emerged from the daily operation of Reena Spaulings Fine Art in New York—a gallery founded by John Kelsey & Emily Sundblad. Both an artist and a dealer, Reena Spaulings’ double identity allows her to play with the art world’s hierarchies and divisions of labour, often with satirical effects. She thus embodies a provisional alternative to the role of the artist demanded by the market and its notions of authenticity.

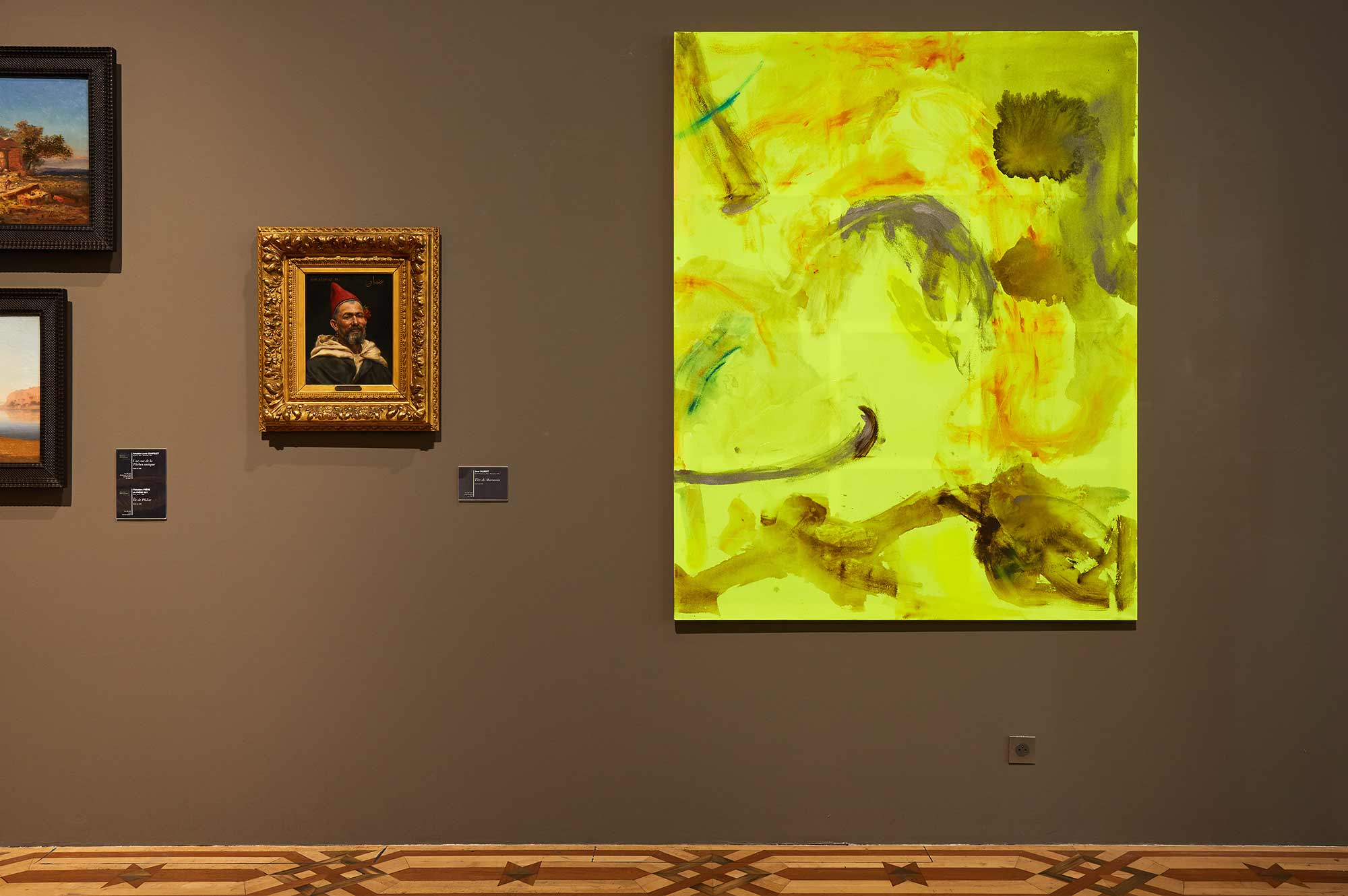

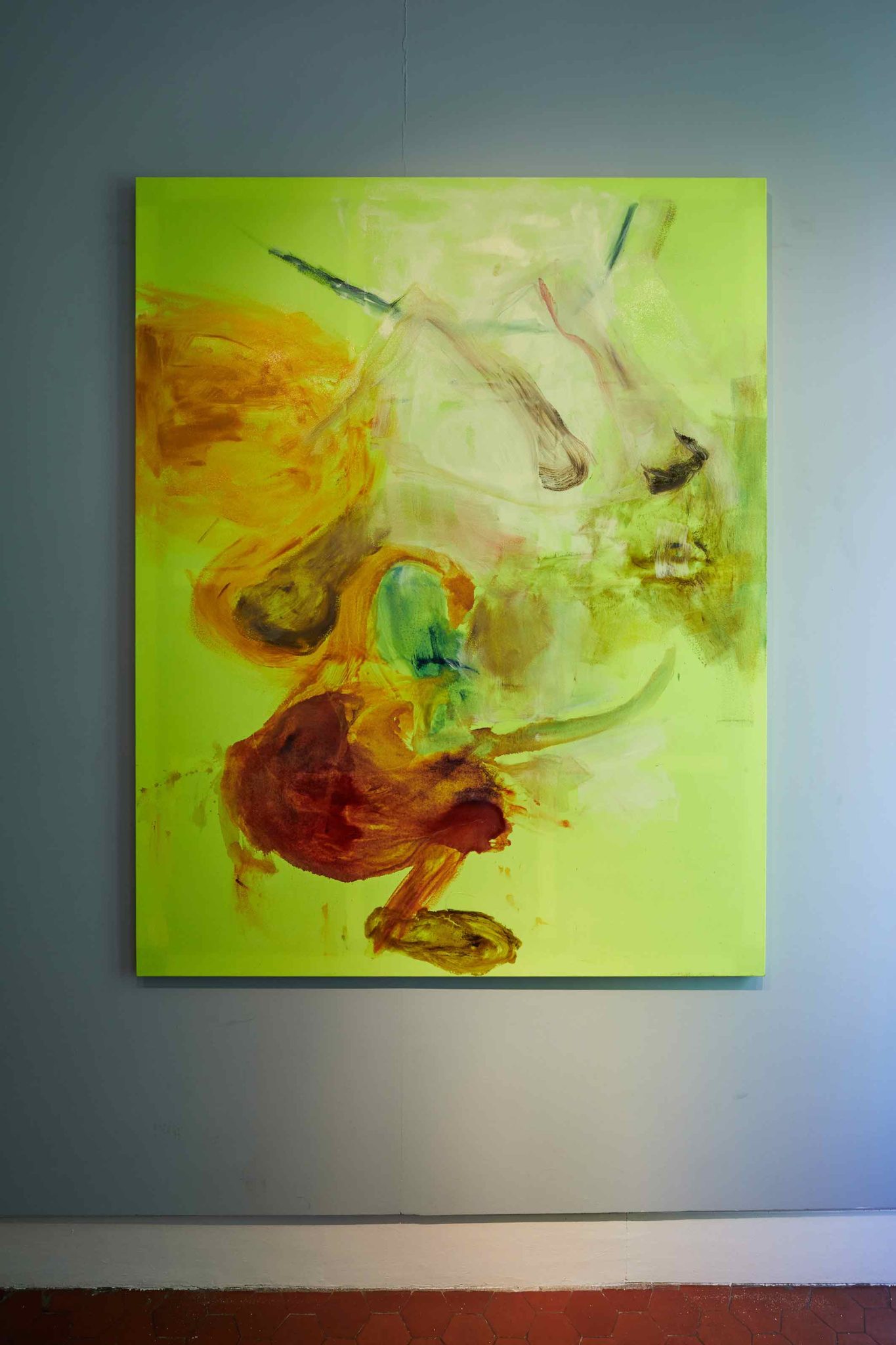

Reena Spaulings, Lion Hunt, 2019

Acrylic and pigment on ‘high visibility’ yellow fabric

Courtesy of the artist and Campoli Presti

Installed throughout all plots of Traits d’union.s, this Lion Hunt (2019) series of paintings takes its cue from Eugène Delacroix’s eponymous work The Lion Hunt (1855), which was severely damaged during a fire at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux in 1870. Delacroix’s original was a throughly orientalist vision of violent conflict between humans and animals structured according to primary colour harmonies: red, yellow, blue. As an artist collective, a fictional persona and gallery founded in post-9/11 New York, Reena Spaulings’ hybrid nature often leads her to play with the social conditions of art itself. Here, Spaulings’ interpretations of Delacroix are all based on a high-visibility yellow. Not only does this palette render traditional colour harmonies impossible, it also evokes the emergency jackets synonymous with the gilets jaunes – a complex protest movement that paralleled the planning of Manifesta 13 Marseille. By this garish sleight of hand, Spaulings seems to draw parallels between visual and social conflict, and much like in Delacroix’s original it remains unclear who the victors will be.

Reena Spaulings, Mollusk (Rosso Francia) and Mollusk (Verde Foresta), 2019

Marble Rosso Francia and Verde Foresta

Courtesy of the artist and Campoli Presti

In the entrance of Musée Cantini, visitors find a series of boogie boards sculpted in marble. Though incongruous at first sight, these works subtly echo the history of the museum, which was named after the wealthy marble manufacturer Jules Cantini, who donated the museum’s present building to the city of Marseille in 1916. Incidentally, these works were produced as part of a deal with another marble manufacturer, Josef Dalla Nogara, who agreed to provide the materials and manufacture the artworks in exchange for few extra works for his collection. Titled Mollusks, the history of these works in tandem with that of the museum cheekily point to the position of art in the broader economy: molluscs are often bottom feeders. Meanwhile, their paradoxical form – boogie boards unable to float – makes them seem more like tombstones than anything else, evoking the commodity as the resting place of dead labour.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz*,Trinh T.Minh-ha & Lynn Marie Kirby,Hannah Black,Reena Spaulings

11.09 - 29.11.2020 The Park: Becoming a Body of Water

Minia Biabiany,Ali Cherri*,Reena Spaulings

25.09 - 29.11.2020 The Park: Becoming a Body of Water

Center for Creative Ecologies*,Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc,Reena Spaulings

25.09 - 29.11.2020 The School: The Sonorous, The Audible, and The Silenced

Yalda Afsah*,Mohamed Bourouissa*,Julien Creuzet*,Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca*,Ymane Fakhir*,Tuan Andrew Nguyen*,Reena Spaulings,Mounir Ayache*

09.10 - 29.11.2020 The Home: Rentals, Experiences, Places

Black Quantum Futurism*,Martine Derain*,Lukas Duwenhögger,Jana Euler,Ken Okiishi*,Cameron Rowland,Reena Spaulings,Arseny Zhilyaev*,Samia Henni*

28.08 - 29.11.2020